Coronavirus and the end of the global supply chain

Posted by Paul Simpson

Coronavirus has shown how fragile our cost-driven, just-in-time processes really are. With practitioners adapting to survive while planning more resilient systems for the future, will procurement ever be the same?

When the first container ship arriving from China at the port of Vancouver was cancelled in January this year, it didn’t seem particularly significant. By mid-March, when China’s struggle with Covid-19, aka coronavirus, had become so all-consuming that 30 more journeys had been cancelled, Vancouver’s port officials were facing a crisis of historic magnitude.

That consumer goods weren’t being unloaded from China as per the schedule was less of a concern than the fact that Canada, which usually filled those containers with lentils and peas, had two months’ worth of crops stuck in port (historically, roughly a third of Canada’s crops have been exported in containers). Imports were also disrupted: one local food company had to pay a premium for spices from Thailand which arrived a month behind schedule. Brazil’s coffee makers suffered too as the missing containers made it hard for them to ship their products to China.

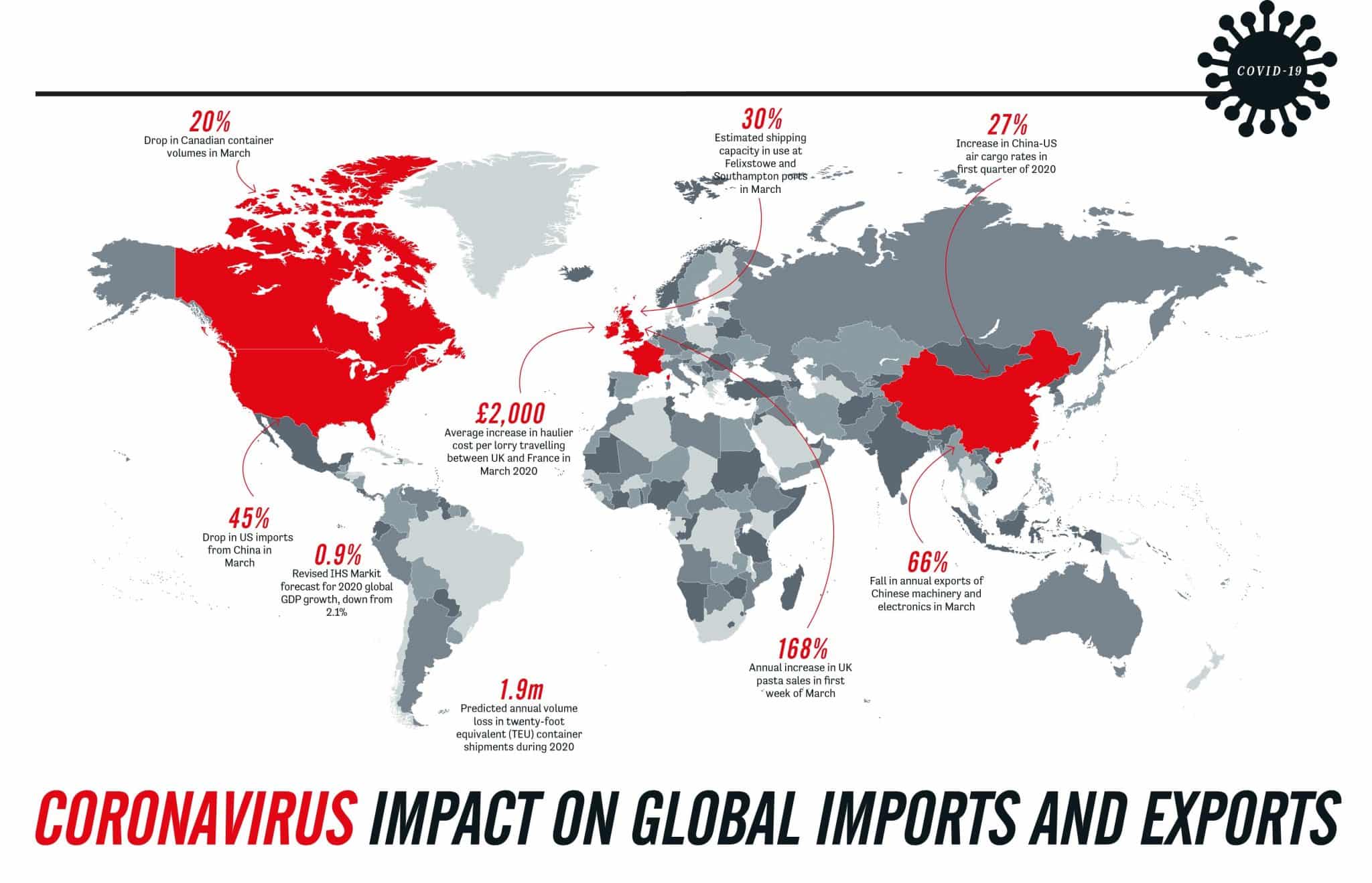

The problems of countries and companies along just one shipping route indicate why some economists, notably Simon MacAdam at consultancy Capital Economics, are predicting a 20% dip in trade volumes this year. That is significantly worse than the last recession in 2009, when volumes fell by 13%.

The bottlenecks in Vancouver did not grab headlines in the same way as various countries’ difficulties in speeding up production of ventilator kits. But as Professor Tim Benton, research director of the Chatham House think tank’s energy, environment and resources programme, says, they remind us: “We have created a global supply chain that, for all its financial efficiencies, has very little resilience.”

Coffee is a case in point. One industry estimate, cited by The Economist, suggests that 29 companies across 18 countries need to collaborate to make “one humble cup”. That may, Benton observes, work financially for the companies concerned – and for consumers who can buy their favourite brand at a lower cost – but it cannot, in any true sense of the word, be described as efficient. A hurricane, strike or outbreak of coronavirus at any of those 29 companies could severely disrupt the supply chain, and the spread of the virus into Latin America has already led to huge spikes in commodity prices as buyers anticipate lockdowns and shuttered businesses. And that’s without the kind of surge in consumer demand that led to a rise of more than 20% in British supermarket sales during March 2020.

All those photographs of empty shelves, explicitly condemning shoppers for panic buying and hoarding, obscure the fact, Benton says, that governments are hoarding too. “Kazakhstan banned exports of wheat flour, Thailand has stopped exporting eggs, Vietnam has suspended rice exports and Russia is talking about limiting grain exports to protect supplies,” he says. “It’s not clear how many more governments will follow suit, but if they keep putting their nation first, the

situation can only get worse.” Protectionist policies, coupled with panic buying, could create a self-perpetuating cycle of rising food prices.

What many analysts referred to as the “hidden costs of globalisation” were becoming visible even before the pandemic struck. “There was a clear sense that we had reached peak globalisation,” says Andrew Missingham, the co-founder of creative management consultancy B+A. “The political shocks of 2016, protectionist trade policies and climate change were already asking fundamental questions about that model.” Some of the foundations which businesses took for granted no longer exist in a pandemic age. “If you look at a business like ours, for example, it was predicated on three factors – the internet, cheap flights and free movement of people – and two of those no longer apply,” says Missingham.

Since the last global economic crisis in 2007-2008, many parts of the procurement profession have performed Herculean labours, protecting profits, companies and jobs by cutting billions of dollars in cost from the world’s supply chains. They did that, primarily, by seeking out places where they could make things at the lowest cost – often in China – and minimising inventory by applying lean manufacturing or ‘just-in-time’ principles.

The result is a global supply chain that is interconnected, intricate and sometimes unfathomable. As Duncan Brock, group director, CIPS, says: “The interwoven nature of modern supply chains means it is almost impossible to say for certain just how reliant we are on China for manufacturing and assembly.” Companies that placed such trust in Chinese suppliers that they used single-sourcing now face severe disruption.

Diverse sourcing strategies

“One key lesson from the pandemic is the importance of spreading the risk,” says Tim Lawrence, supply chain expert at PA Consulting. “Companies should avoid clustering suppliers in one region and around similar supply chains, reconsider whether it makes sense to create isolated supply chains and understand the location risks in every tier of the supply chain. Your supply chain may not be as diverse as you like to think – for example, your alternative suppliers may themselves be reliant on tier 3 or tier 4 suppliers in the same region.”

The obvious, if laborious, way to avoid such problems is to map your supply chain. “It isn’t easy,” admits Lawrence.

“It took Airbus five years to do it with the A320 passenger aircraft. And supply chains change so fast that the map might be out of date on the day you complete it, but digital technologies – especially 5G, data analytics and artificial intelligence – are proving increasingly helpful. They can improve visibility and connectivity, generate early warnings, and help free up supply chain leaders to focus on the strategic issues.”

Strategic questions would include assessing when it makes sense to keep the supply chain within the business. “There are certain components that are so critical to the business that the most secure supply chain might be to vertically integrate them,” says Lawrence.

As global supply chains hit bottlenecks many neither envisaged or expected, Missingham predicts: “We will see a lot more decentralisation, regionalisation and localisation.” Some pundits have talked of a ‘great reset’, where reshoring becomes the new norm. In an increasingly automated workplace, labour costs are no longer as critical when locating factories. Last year, multinational toolmaker Stanley Black & Decker shifted production of its Craftsman tools from China to Fort Worth, Texas, without increasing costs.

Brock expects new sourcing strategies to emerge but warns that any ‘reset’ will take time: “This may be the last straw for global sourcing as supply chain managers look local but, to put this in context, 290 of Apple’s 800 suppliers are based in China so such a strategy would take years to implement.”

Diversifying a supplier base is not always straightforward. Companies may be required, Brock says, to form alliances within their sector to develop new sources of supply where choice is limited or existing suppliers are clustered in the same region. Unilever has opted to protect the suppliers it already has, announcing a £420m cashflow relief scheme to expedite payments to SMEs in its network and offering credit to small retailers.

Learning just in time

Just-in-time manufacturing – reducing inventories to 15-30 days of stock or even less – has been a multi-billion-dollar boon for the global economy. Lawrence does not foresee a wholesale rejection of just-in-time or lean, but a reappraisal based on a more realistic assessment of the potential cost to the business: “There will be certain components and materials where you decide that it is more efficient, in the broad sense, to have six to eight weeks’ stock than three or four.”

Popularised by Robert Hall in his 1987 book Zero Inventories, the just-in-time philosophy always sat uncomfortably alongside procurement’s cautious ‘just in case’ approach to buying inventory. Dazzled by the savings, many companies ignored the fact just-in-time made it much harder for procurement to understand how extensive, responsive and opaque supply chains really were. This truth came home in February when a South Carolina hospital ran out of surgical gowns. Its traditional supplier in China had contamination concerns over its stock – not related to coronavirus – but when managers tried to buy replacements, with the pandemic escalating, they struggled.

But in the middle of a crisis this severe, there is also a temptation to overestimate how profoundly our behaviour as individuals, companies and organisations will change. The 2007-2008 depression signalled, as so many people forecast at the time, the end of the road for a certain type of free market capitalism. It seemed a reasonable proposition at the time but it didn’t work out that way. The idea of getting back to ‘business as usual’ can induce a certain complacency.

In this crisis, many managers – not just in procurement – will argue that nobody could have seen this coming. That is true, up to a point. Nobody could have predicted how quickly and radically Covid-19 would change the way we live and work. Yet, for those companies which were paying attention, the signs were there to be interpreted.

The US grocery chain H-E-B began monitoring what was happening in China in the second week of January. After two weeks of analysing various sourcing reports and maintaining close, constant contact with companies in China, the retailer redrafted the disaster plans it had used for the swine flu outbreak in 2009 and Hurricane Harvey in 2017 to confront coronavirus.

As Craig Boyan, H-E-B’s president, told Texas Monthly: “Chinese retailers sent some pretty thorough information about the early days of the outbreak, how that affected grocery retail, how employees were addressing sanitisation and social distancing, how quarantine affected the supply chain, how shopping behaviour changed and what steps they wished they’d taken to get ahead earlier in the cycle.”

Using that information, H-E-B promptly took various steps: forming a remote working committee to coordinate policy and actions, reducing opening hours to give more time to put product on shelves, rationing certain product purchases and paying local beer distributors to bring eggs to its stores. Even so, Boyan admits, they did not resolve every challenge: “We’re still struggling to get eggs and we still have a hard time understanding why toilet rolls were the first things to go out of stock.”

Planning to fail

If the coronavirus is a black swan event, there is an obvious temptation to plan on the basis that it will never happen again – or at least not in our working lives. The call of the next quarter’s targets can often sound more compelling, but Lawrence says supply chain leaders need to change their mindset. “It is easy to focus on the small things that happen often, or may come up in the next three to six months, and plan scenarios for those, but to be honest you could delegate that task to the technology. As this pandemic shows, it would pay companies to look at the really big things that don’t happen very often and run scenarios for those.”

Understanding risk is partly about what supply chain leaders know but also, Missingham says, about what they do with what they know: “People working in supply chains are, in my experience, real experts in the people, challenges and opportunities they face – be that individual components or particular raw materials. The problem is that that knowledge is too narrowly held within organisations. In future, one of the important jobs for supply chain specialists will be to educate a broader part of the business.”

Covid-19 has shed an unforgiving light on every flaw in the world’s supply chain. The pandemic has shut factories, stalled shipments, fuelled labour shortages, closed borders and will, the United Nations estimates, cost the global economy at least $1trn. “In times of crisis and uncertainty, it is hard for businesses to plan but supply chain managers who act now and keep a close eye on such data as the purchasing managers indices as they make plans can mitigate the damage,” says Brock.

Yet in future, when supply chain leaders have the breathing space to think, let alone plan, for the long term, they might conclude that prevention is the best form of mitigation. Companies which neglect the opportunity to fundamentally rethink their supply chains do so at their own peril.

That is especially true, Benton argues, when it comes to defining a more sustainable, healthy and environmentally friendly food production system.

As he says: “The question is not ‘will it happen?’ The question is ‘when will it happen?’ We could have started to create a sustainable, equitable and nutritious food system in 2003, after the outbreak of SARS. It could happen now or it could happen in 10 years’ time when the next crisis occurs, but for the sake of our health, and the health of our planet, it cannot not happen.” What goes for the food industry, you suspect, goes for the other sectors of the global economy.

Article originally published on https://www.cips.org/supply-management/analysis/2020/april/the-end-of-the-global-supply-chain/